If someone asked you for a world famous Olympic athlete you probably wouldn’t give the name Peter Norman.

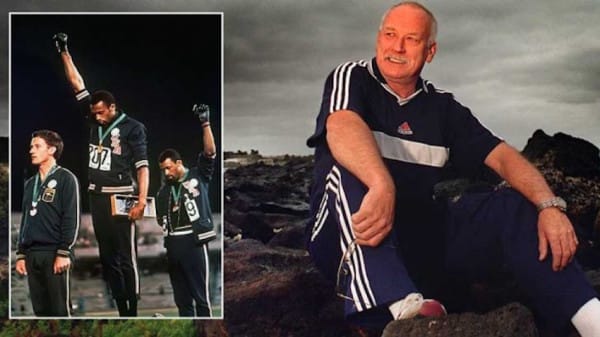

Even though he’s been featured in one of the most iconic images to come out of the Olympics, Peter Norman and his incredible story appear to have been lost to time itself.

It was the summer of 1968 and the Summer Olympics were all anyone could talk about. Tommie Smith broke world records during the 200-meter dash finals. He earned his gold medal by completing the dash in just 19.83 seconds!

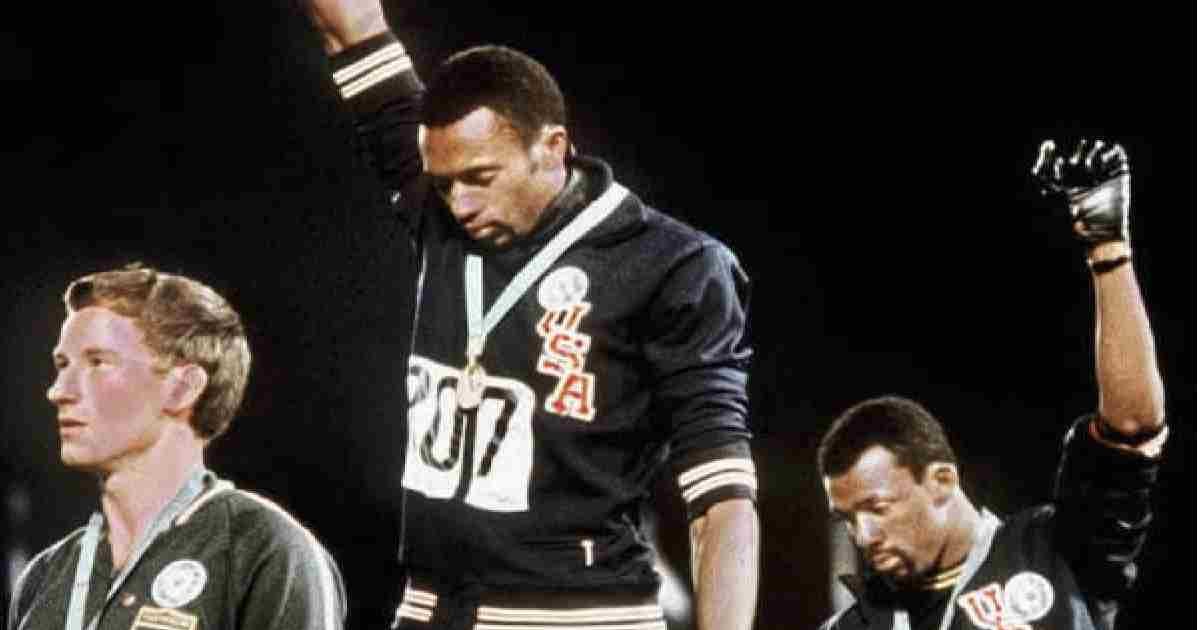

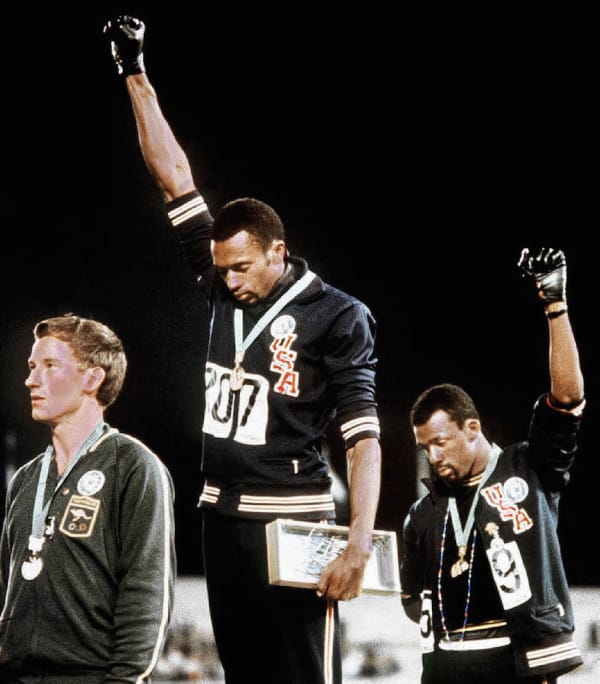

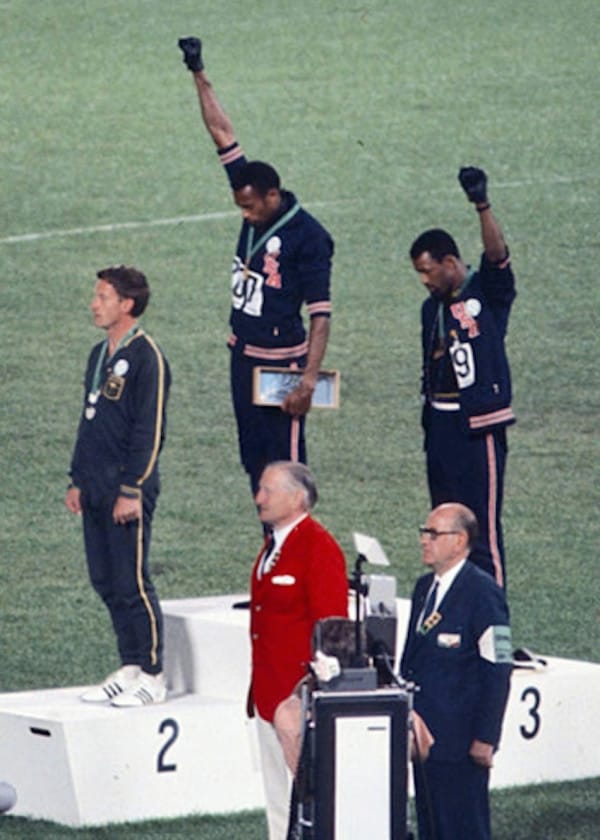

But what had the most people talking wasn’t his amazing run, but instead what he did during the awards ceremony. Alongside John Carlos, a fellow runner in the 200 meter dash, Smith did a Black Panther salute, barefoot when he was given his Olympic medal.

The salute was a silent protest against the injustices suffered by the African American community in the 1960s. The iconic photograph was the subject of much controversy at the time, but has since become a symbol of the Civil Rights Movement in political history.

While Carlos and Smith attracted all of the attention, there was actually a third person on that podium. A man named Peter Norman who everyone just seemed to ignore.

Due to Norman’s unusual posture and his face expressing little to no emotion, most people simply ignored him. When people did notice him, though, they just thought that he looked like he didn’t belong, as if he was oblivious to what was happening right behind him.

[rsnippet id=”4″ name=”DFP/34009881/Article_1″][rsnippet name=”universal-likebox” multi-site=”true”]

For Italian writer Riccardo Gazzaniga, however, this only made him more interested. So Gazzaniga dug to find the truth behind the white man featured in this photo and learn what his story was. In an article titled “The White Man in That Photo”, Peter Norman and his incredible story are finally getting the recognition that he deserved. He is now being hailed as “the third hero of that night in 1968,” all these years later.

Below is a reprinting of Gazzaniga’s article with correct attribution. Thanks to Films For Action for sharing this incredible story.

Sometimes photographs deceive. Take this one, for example. It represents John Carlos and Tommie Smith’s rebellious gesture the day they won medals for the 200 meters at the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City, and it certainly deceived me for a long time.

I always saw the photo as a powerful image of two barefoot black men, with their heads bowed, their black-gloved fists in the air while the US National Anthem, “The Star-Spangled Banner,” played. It was a strong symbolic gesture — taking a stand for African American civil rights in a year of tragedies that included the death of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy.

It’s a historic photo of two men of color. For this reason I never really paid attention to the other man, white, like me, motionless on the second step of the medal podium. I considered him as a random presence, an extra in Carlos and Smith’s moment, or a kind of intruder.

Actually, I even thought that that guy — who seemed to be just a simpering Englishman — represented, in his icy immobility, the will to resist the change that Smith and Carlos were invoking in their silent protest. But I was wrong.

Thanks to an old article by Gianni Mura, today I discovered the truth: that white man in the photo is, perhaps, the third hero of that night in 1968. His name was Peter Norman, he was an Australian that arrived in the 200 meters finals after having ran an amazing 20.22 in the semi finals. Only the two Americans, Tommie “The Jet” Smith and John Carlos had done better: 20.14 and 20.12, respectively.

Norman was a white man from Australia, a country that had strict apartheid laws, almost as strict as South Africa.

There was tension and protests in the streets of Australia following heavy restrictions on non-white immigration and discriminatory laws against aboriginal people, some of which consisted of forced adoptions of native children to white families.

The two Americans had asked Norman if he believed in human rights. Norman said he did. They asked him if he believed in God, and he, who had been in the Salvation Army, said he believed strongly in God. “We knew that what we were going to do was far greater than any athletic feat, and he said, “I’ll stand with you” — remembers John Carlos — “I expected to see fear in Norman’s eyes, but instead we saw love.”

[rsnippet id=”5″ name=”DFP/34009881/Article_2″]

Smith and Carlos had decided to get up on the stadium wearing the Olympic Project for Human Rights badge, a movement of athletes in support of the battle for equality.

They would receive their medals barefoot, representing the poverty facing people of color. They would wear the famous black gloves, a symbol of the Black Panthers’ cause. But before going up on the podium they realized they only had one pair of black gloves. “Take one each,” Norman suggested. Smith and Carlos took his advice.

But then Norman did something else. “I believe in what you believe. Do you have another one of those for me?” he asked pointing to the Olympic Project for Human Rights badge on the others’ chests. “That way I can show my support in your cause.” Smith admitted to being astonished, ruminating: “Who is this white Australian guy? He won his silver medal, can’t he just take it and that be enough!”

Smith responded that he didn’t, also because he would not be denied his badge. There happened to be a white American rower with them, Paul Hoffman, an activist with the Olympic Project for Human Rights. After hearing everything he thought “if a white Australian is going to ask me for an Olympic Project for Human Rights badge, then by God he would have one!” Hoffman didn’t hesitate: “I gave him the only one I had: mine.”

The three went out on the field and got up on the podium: the rest is history, preserved in the power of the photo. “I couldn’t see what was happening,” Norman recounts, “[but] I had known they had gone through with their plans when a voice in the crowd sang the American anthem but then faded to nothing. The stadium went quiet.”

It seemed as if the victory would be decided between the two Americans. Norman was an unknown sprinter, who seemed to just be having a good couple of heats. John Carlos, years later, said that he was asked what happened to the small white guy — standing at 5’6” tall, and running as fast as him and Smith, both taller than 6’2”.

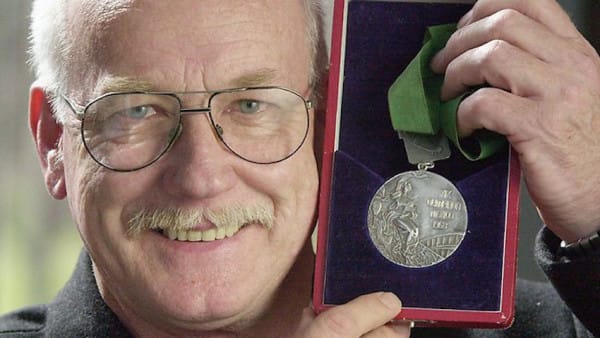

The time for the finals arrives, and the outsider Peter Norman runs the race of a lifetime, improving on his time yet again. He finishes the race at 20.06, his best performance ever, an Australian record that still stands today, 47 years later.

[rsnippet id=”6″ name=”DFP/34009881/Article_3″]

But that record wasn’t enough, because Tommie Smith was really “The Jet,” and he responded to Norman’s Australian record with a world record. In short, it was a great race.

Yet that race will never be as memorable as what followed at the award[s] ceremony.

It didn’t take long after the race to realize that something big, unprecedented, was about to take place on the medal podium. Smith and Carlos decided they wanted to show the entire world what their fight for human rights looked like, and word spread among the athletes.

The head of the American delegation vowed that these athletes would pay the price their entire lives for that gesture, a gesture he thought had nothing to do with the sport. Smith and Carlos were immediately suspended from the American Olympic team and expelled from the Olympic Village, while the rower Hoffman was accused of conspiracy.

Once home, the two fastest men in the world faced heavy repercussions and death threats.

But time, in the end, proved that they had been right and they became champions in the fight for human rights. With their image restored they collaborated with the American team of Athletics, and a statue of them was erected at the San Jose State University. Peter Norman is absent from this statue. His absence from the podium step seems an epitaph of a hero that no one ever noticed. A forgotten athlete, deleted from history, even in Australia, his own country.

Four years later at the 1972 Summer Olympics that took place in Munich, Germany, Norman wasn’t part of the Australian sprinters team, despite having run qualifying times for the 200 meters thirteen times and the 100 meters five times.

Norman left competitive athletics behind after this disappointment, continuing to run at the amatuer level.

Back in the change-resisting, whitewashed Australia he was treated like an outsider, his family outcasted, and work impossible to find. For a time he worked as a gym teacher, continuing to struggle against inequalities as a trade unionist and occasionally working in a butcher shop. An injury caused Norman to contract gangrene, which led to issues with depression and alcoholism.

As John Carlos said, “If we were getting beat up, Peter was facing an entire country and suffering alone.” For years Norman had only one chance to save himself: he was invited to condemn his co-athletes, John Carlos and Tommie Smith’s gesture in exchange for a pardon from the system that ostracized him.

A pardon that would have allowed him to find a stable job through the Australian Olympic Committee and be part of the organization of the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games. Norman never gave in and never condemned the choice of the two Americans.