Watch the exciting news in the video below.

[rumble video_id=v59huz domain_id=u7nb2]

Researchers say that one-third of UK consumers throw food away just because they have reached the “use-by” date. However, sixty percent of the food that is thrown away each year, representing 4.2 million tons, is actually still safe to eat. That’s a lot of perfectly good food that goes to waste.

Food technologists introduced use-by dates in order to improve food safety. Currently, consumers only have use-by dates to go by or even “sniff tests” just to judge if it’s safe to eat their food. But use-by dates don’t account for factors such as processing and storage conditions which can lead both consumers and retailers to throw food away even if they’re still perfectly safe to eat.

Since most of the food that is thrown away is packaged in plastic, the practice also compounds plastic pollution.

Giandrin Barandun, from Imperial College London’s Department of Bioengineering, said: “Use-by dates estimate when a perishable product might no longer be edible — but they don’t always reflect its actual freshness.

“Although the food industry — and consumers — are understandably cautious about shelf life, it’s time to embrace technology that could more accurately detect food edibility and reduce food waste and plastic pollution.”

Despite its limitations, there has been no commercially viable and reliable alternative to the use-by date. At least, until now.

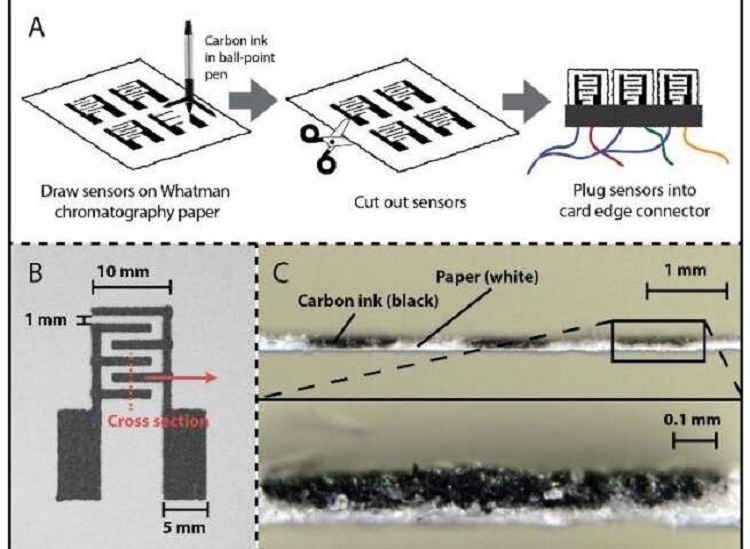

Researchers at Imperial College London, one of whom is Barandun, managed to develop what is called “paper-based electrical gas sensors” or PEGS and they say the prototype sensors cost a mere two US cents to manufacture. The sensors detect gases such as ammonia and trimethylamine, common spoilage gases, in fish and meat products.

An app on a smartphone can read the sensor data so all consumers or shop assistants need to do is scan the packaging through their smartphone and they’ll know if it’s safe to eat the food.

The sensors were made by printing carbon electrodes onto cellulose paper. The materials are biodegradable and non-toxic, so not only are they eco-friendly, but they are also safe for use in food packaging. The sensors are paired to “near field communication (NFC)” tags which are a series of microchips that allow nearby mobile devices to read the data.

During laboratory tests, PEGS managed to quickly pick up even trace amounts of spoilage gases on packaged chicken and fish. They were more accurate than existing sensors but only cost a fraction of the price.

If PEGS manages to replace the use-by date, its lower cost may also lead to lower food prices, a double win for consumers.

Dr. Firat Güder, also of Imperial’s Department of Bioengineering and the study’s lead author, said: “Although they’re designed to keep us safe, use-by dates can lead to edible food being thrown away.

In fact, use-by dates are not completely reliable in terms of safety as people often get sick from food-borne diseases due to poor storage, even when an item is within its use-by.

“Citizens want to be confident that their food is safe to eat, and to avoid throwing food away unnecessarily because they aren’t able to judge its safety. These sensors are cheap enough that we hope supermarkets could use them within three years.

“Our vision is to use PEGS in food packaging to reduce unnecessary food waste and the resulting plastic pollution.”

Just how effective is PEGS compared to currently available on the market?

- Most sensors struggle to function above 90 percent humidity but PEGS is still effective at nearly 100 percent humidity.

ADVERTISEMENT - Don’t need to be heated because they work at room temperature, so only low amounts of energy are used.

- Only react to gases associated with spoilage, unlike existing sensors that are apt to return false positives.

The authors are now planning to broaden the scope of PEGS by making them applicable to other types of food and industries.

Depending on the type of food, a new array of sensors will return different signals for different gases and/or changing humidity.

The new sensors may also have other applications such as detecting chemicals in agriculture, detecting disease markers through breath (like in kidney disease), or determining air quality.

The Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) funded the work and the study was published in ACS Sensors.