The world has changed considerably over the last few centuries, this is what Our World in Data shows.

One thing, however, has remained constant through this transition: we all have to die sometime. However, the causes of death are changing as living standards improve, healthcare advances, and lifestyles change.

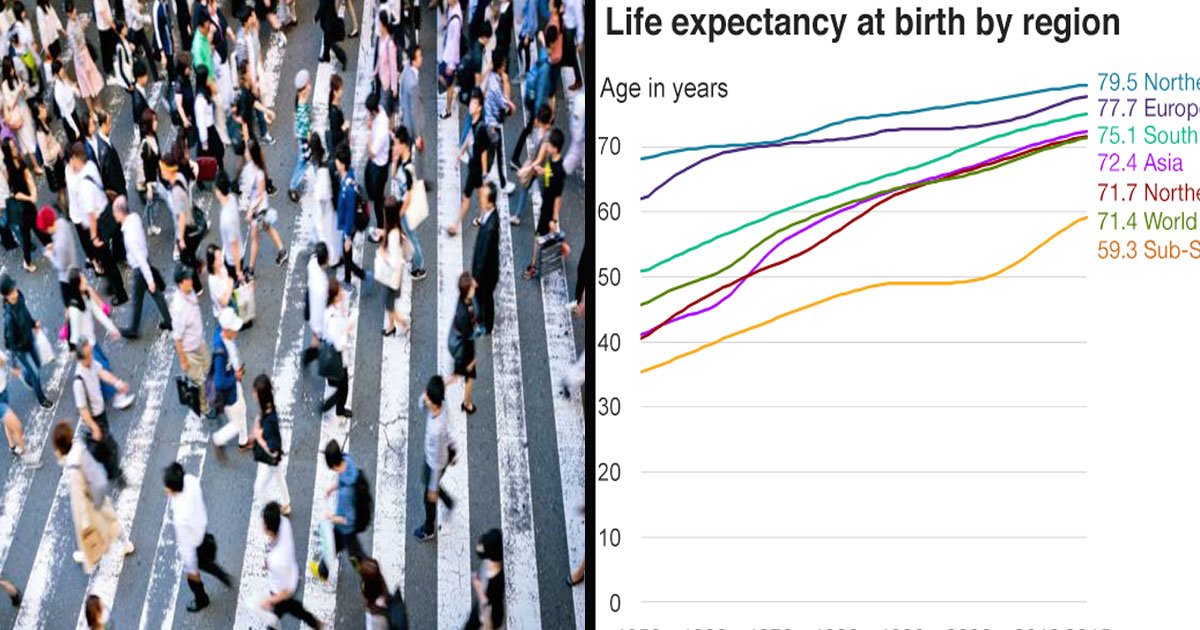

In 1950, the global average life expectancy at birth was only 46. By 2015, it had shot up to over 71.

In some countries, progress has not always been smooth. Disease, epidemics and unexpected events are a reminder that ever-longer lives are not a given.

Meanwhile, the deaths that may preoccupy us – from terrorism, war and natural disasters – make up less than 0.5% of all deaths combined.

But across the world, many are still dying too young and from preventable causes.

The story of when people die is really a story of how they die, and how this has changed over time.

Cause-of-death statistics help health authorities determine the focus of their public health actions. A country in which deaths from heart disease and diabetes rise rapidly over a period of a few years, for example, has a strong interest in starting a vigorous programme to encourage lifestyles to help prevent these illnesses.

Similarly, if a country recognizes that many children are dying of pneumonia, but only a small portion of the budget is dedicated to providing effective treatment, it can increase spending in this area.

High-income countries have systems in place for collecting information on causes of death. Many low- and middle-income countries do not have such systems, and the numbers of deaths from specific causes have to be estimated from incomplete data. Improvements in producing high-quality cause-of-death data are crucial for improving health and reducing preventable deaths in these countries.

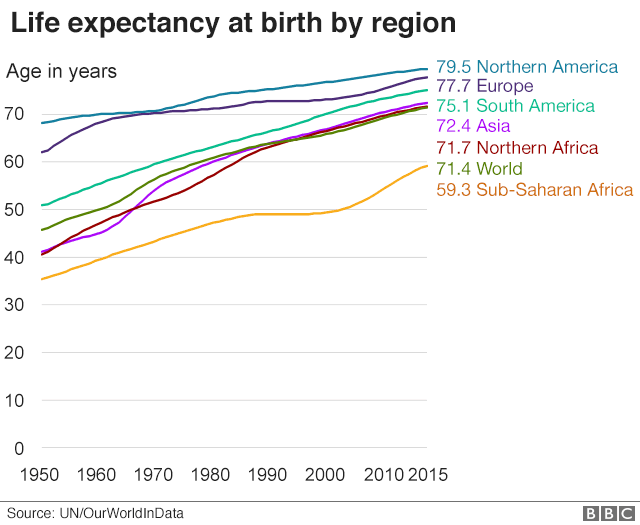

Global deaths: In 2016, around 55 million people died – nearly half of these were aged 70 years or older; 27% aged 50-69; 15% aged 15-49; only 1% aged 5-14; and around 10% were children under the age of 5. In the chart below we see a breakdown of global deaths by cause, ordered from highest to lowest.

This is shown in absolute numbers and each cause as a share of total deaths. Note that this list is not exhaustive: deaths from less common causes are not shown. You can also the causes of death for any country by clicking on the chart to get to the interactive version of this chart and then choosing ‘Change country’.

The leading global killer in 2016 were cardiovascular diseases (CVD), which refer to a range of diseases that affect the heart and blood vessels: These include hypertension (high blood pressure); coronary heart disease (heart attack); cerebrovascular disease (stroke); heart failure; and other heart diseases. Cardiovascular diseases killed 17.6 million people – around one-third of all deaths.

Cancers were the second largest, claiming around 9 million (16 percent or every sixth death globally).

Rounding off the top four were respiratory and diabetes-related diseases. Collectively, these are known as non-communicable diseases (NCDs): together they accounted for more than 39 million deaths (more than 70 percent) in 2016.

There are a number of causes with high death tolls which if not entirely preventable can be (and have been in many countries) dramatically reduced. More than 1.7 million newborns still died due to complications at birth.

The very low neonatal death rates in high-income countries and significant progress across the world in recent decades is a testament to the fact that we know how to reduce such tragedies significantly.

Similarly, diarrheal diseases — which claimed 1.7 million people in 2016 and is one of the leading causes of death in children under 5 years old — are also preventable and treatable through improved water, sanitation, hygiene, and simple ‘oral rehydration salt’ (ORS) packets.

Malaria has been successfully eliminated in some regions, and should with time be possible to eradicate; nonetheless, the IHME’s Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study estimates that more than 700,000 still died from malaria in 2016.

Road incidents fall within the top ten causes of death, claiming 1.3 million in 2016.

Surprising to some is that the number who die from suicide is more than double that of homicide at a global level. In fact, the number of deaths from suicides is higher than the number of deaths from all forms of violence – including homicide, terrorism, conflict, and executions – globally and across many countries across the world.

You can see this relationship here. As Yuval Noah Harari notes in his TED Dialogue: “Statistically you are your own worst enemy. At least, of all the people in the world, you are most likely to be killed by yourself”.

At the bottom of the list, we see deaths from natural disasters and terrorist attacks. Whilst the relative risk from such events is typically low, we must take care when using annual statistics in this case. Death rates related to disease, illness and other health factors tend to change relatively slowly over time.

Natural disaster and terrorism-related deaths are different: they can vary substantially from one year to the next. This can make the annual comparison of deaths between health-related factors and volatile events more challenging and assessing the relative risk of these events can require a longer-term overview of high and low-mortality years. We cover discussion and analysis on this topic in a blog post here.

Children are particularly vulnerable to infectious diseases. As recently as the 19th Century, every third child in the world died before the age of five.

Child mortality rates have fallen significantly since then thanks to vaccines and improvements in hygiene, nutrition, healthcare, and clean water access.

Child deaths in rich countries are now relatively rare, while the poorest regions today have child mortality rates similar to the UK and Sweden in the first half of the 20th Century, and are continuing to catch up.

Further to go: Today’s overall picture is positive: we are living longer lives while fewer people – especially children – are dying from preventable causes. But it’s also true that we still have a long way to go.

Further improvements in sanitation, hygiene, nutrition, vaccination, and basic healthcare are all crucial to this.

So too are increased safety measures and mental health provision.

Understanding what people die from is crucial if we want this recent progress to continue.

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organization.

Hannah Ritchie is an Oxford Martin fellow and is currently working as a researcher at OurWorldinData.org. This is a joint project between Oxford Martin and non-profit organization Global Change Data Lab, which aims to present research on how the world is changing through interactive visualizations.

Recommended Video – “Dynamo- The Magician Impossible Looks Healthier Amid The Ongoing Battle With Crohn’s Disease”